Blog

Did goats cause the collapse of the Roman Empire?

Climate change, deforestation, habitat reduction, river pollution, air pollution, microplastics…The damage humanity is wreaking on the environment—and an awareness of that damage—are key aspects of modern life.

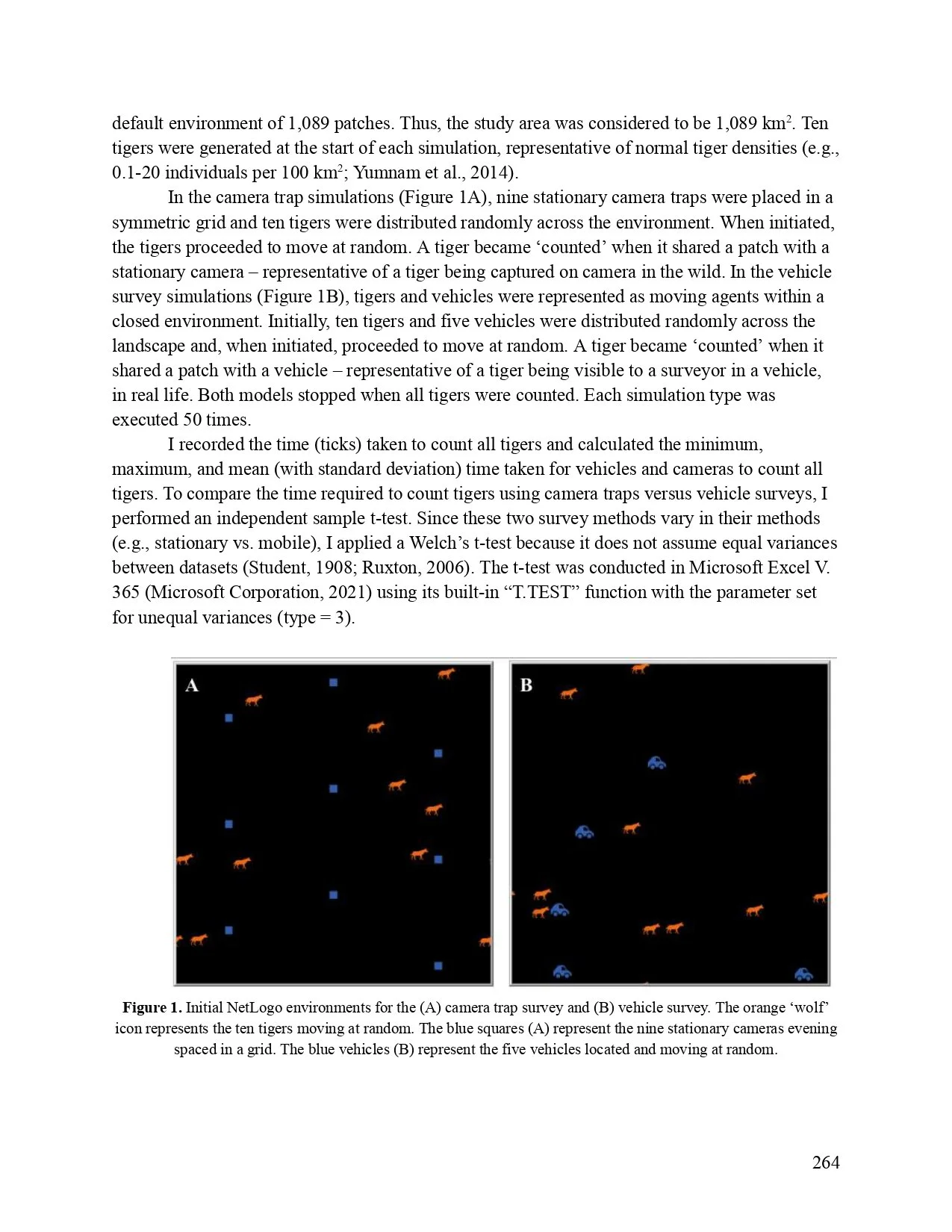

Yet our conception of nature is older than you might expect. So, in fact, is humanity’s thinking about environmental preservation—and its practice of environmental destruction.

In ancient Greece, nature wasn’t something separate from humanity. Everything was a part of physis, a word which referred to the dynamic processes (from the verb phuô, or ‘grow’/’spring forth’) that governed the universe and helped make the conditions that supported human life. There was a fine line between physis and nomos, or the “law” or “custom” by which humans governed themselves.

Greek life revolved around nature, since it was a fundamentally agricultural society. To be a good farmer was, at least according to Hesiod, to be a good person, attentive to the weather (which could express the will of the gods), the changing of the seasons, and so on. Farmers cultivated the land to sustain themselves rather than to generate big profits. Religion also had implications for the environment: sacred groves were carefully preserved. Erysichthon, the son of the King of Thessaly, was punished with never-ending hunger after cutting wood from the grove of Demeter to use to build a large dining hall in his palace. Tortoises were preserved in a grove in Arcadia sacred to Pan; similarly, you weren’t allowed to kill owls (sacred to Athena) in Athens.

There was consciousness of environmental change: Plato’s Critias describes how “compared to the land it once was, Attica of today is like the skeleton revealed by a wasting disease, once all "the rich topsoil has been eroded and only the thin body of the land remains.” But it doesn’t seem that humans were thought to be able to change the environment permanently.

The Romans had a rather clearer view of nature as something to be mastered by humanity. In “On the Nature of Things,” Lucretius describes how early humans learned from nature to refashion their environment: “They created landscapes such as we see today—landscapes rich in delightful variety, attractively dotted with sweet fruit trees and enclosed with luxuriant plantation.” Domestication, and landscaping, was a way in which humanity could be like the gods. “Total dominion over the produce of the earth lies in our hands,” says Balbus in Cicero’s dialogue “On the Nature of the Gods.”

This practical mindset also extended to preventing environmental degradation. Agricultural writers advised the rotation of crops to prevent erosion, and in general careful thinking about what would grow best in specific climates. Pliny complained about the pollution of rivers.

But the ancients did have massive impacts on the natural world around them. Many of the hills of Greece were once covered with trees, and overgrazing on recently cleared land could render the deforestation permanent. Goats, by far the most popular grazing animal in the ancient world, famously eat up anything and everything. The decline of the Roman Empire was in part caused by the exhaustion of the soil and the elimination of its forests. In their drive to dominate nature, the Romans did not strike the appropriate balance.

That’s a useful lesson to keep in mind today, particularly as environmental preservation is getting overshadowed by more pressing political concerns. If the Roman Empire couldn’t resist the natural forces they unleashed by modifying the environment on a much smaller scale, how can we?